"I am involved in history"

Examining the history of our values as a country with a mass shooting problem, and exploring what we can do about it with some help from Wendell Berry.

How did we get here?

How did we come to place more value on gun ownership than children's lives?

How can the safety of hundreds of thousands of schools be stalled by 50 senators refusing to budge?

These were the questions circling my head lying in bed as I woke up the morning of May 25, 2022. The morning after the Uvalde shootings.

How is it legal for this child to own an assault rifle?

How did we get here?

................

This isn't the first time I've asked myself the "how did we get here?" question.

When we continue raping the earth of her fossil fuels instead of creating even the smallest changes for the protection of our earth, I ask myself "how did we get here?"

When we refuse to pass legislation to help our country's marginalized people from getting healthcare, I ask myself, "how did we get here?"

When the wealthiest 10% of US families own 76% of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 50% of families own 1% of the country’s wealth1, I ask myself, "how did we get here?"

Is this the result of a few bad apples put in charge? Are we just a country of selfish jerks? Is it the internet's fault? Did our morals go horribly awry sometime in the past few decades? How did we get here?

(And does the reason rhyme with Shonald Shrump?)

Wendell Berry gives us a history lesson in US values

In trying to trace back some kind of historical trail of bread crumbs this week, a book I read a few years ago came to mind: The World-Ending Fire by Wendell Berry.

I still had the book on Audible, so I re-listened this past week. One of his essays included in the book, A Native Hill, written in 1968 struck me as especially relevant this week.

Wendell Berry, a farmer from Kentucky, had the same “how did we get here?” question when he looked out over his Kentucky farmland devastated by topsoil erosion and industrialization. He wondered if there was some recent error in judgment as he watched farmers valuing short-term profits over the long-term health of the land again and again and again.

His question led him to the book "The History of Kentucky" which describes the industrialization of the very county land that Berry farms.

The book includes an account from 1797 of Reverend Jacob Young, who wrote of a three-day job he joined to help construct a road through New Castle, Kentucky.

After reading the book, Wendell Berry wrote,

"The [Indigenous peoples] who had the wisdom and grace to live in this country for ten thousand years without destroying or damaging any of it, needed for their travels no more than a footpath; but their successors, who in a century and a half plundered the area of at least half of its topsoil and virtually all of its forest, felt immediately that they had to have a road."

Berry notes that Native Americans would have built a small shelter and a small fire if they were traveling through, but the Kentucky road-builders "felled hickory trees in great abundance; made great log heaps... and caused them to burn rapidly.' Far from making a small shelter that could be adequately heated by a small fire, their way was to make no shelter at all, and heat instead a sizeable area of the landscape. The idea was that when faced with abundance, one should consume abundantly--an idea that has survived to become the basis of our present economy."

Reading of the history of Kentucky helped Berry realize, the way the farmers in the 20th century treated the land was not solely born out of their own greed or selfishness, but could be directly traced to the values imbued in them by their ancestors. Values of control, conquest and limitless economic expansion.

Farmers thoughtlessly cut down hills and forests in their way as thoughtlessly as their predecessors cut down trees in theirs. The difference between their ancestors and them wasn’t some radical shift in morals; the difference is today, we have more advanced technology to carry out conquest and expansion.

In reading Berry's realization, my own light bulb went off.

Our current epidemic of mass shootings goes deeper than a modern mental health crisis, a loss of morality or Donald Trump stoking the fire of extremism. We continue to reap the seeds sown centuries ago. Seeds of valuing limitless expansion- conquest, violence and economic growth. Seeds woven into the foundation of our country.

Berry's account of the 1797 road-building expedition turning violent for amusement offers a chilling example. In Jacob Young's own words, this was what happened the first night this group of strangers camped together:

"we spent the evening in hearing the hunter's stories relative to the bloody scenes of the Indian War...... They became very rude, and raised the war-whoop.... They chose two captains, divided the men into two companies and began fighting. They fought for two or three hours... some were severely wounded, blood began to flow freely..."2

Of this incident Berry says:

"the significance of this bit of history is its utter violence. The work of clearing the road was itself violent. And from the orderly violence of that labor, these men turned for amusement to disorderly violence. They were men whose element was violence.... and let us acknowledge that these were truly influential men in the history of Kentucky, as well as in the history of the most of the rest of America.... Their reckless violence has glamorized all our trivialities and evils.... Their war whoop has sanctified our inhumanity and ratified our blunders of policy."

Glamorizing reckless violence? Wow does that sound familiar. The violent bell these influential men rang when they turned to violence for amusement still echoes today. So much of our modern amusement is violent: Marvel movies, wrestling, Fortnite, boxing, James Bond, hunting, Grand Theft Auto.

Reverend Jacob Young reminded me ours is far from the first gun-obsessed generation of Americans:

"The costume of the Kentuckians was a hunting shirt, buckskin pantaloons, a leathern belt around their middle, a scabbard and a big knife fastened to their belt.... They did not think themselves dressed without their powder-horn and shot-pouch, or the gun and the tomahawk. They were ready, then, for all alarms."

Ready for all alarms.

That sounds familiar. Rally cries to be ready for all alarms can be heard all over conservative news outlets the past two weeks- answering guns with more guns, violence with more violence. Be ready. Be prepared. Be armed.

The thing the men in the 1790s failed to acknowledge was that the reason for needing protection in the first place was in fact, the presence of their own guns. Their guns started the fight. Not the Indigenous people. This spiral of needing more guns was in and of itself born from their own guns.

It's not difficult to see the parallels to today.

We are not the first generation of Americans dealing with a gun problem. The difference is, now our guns are much more deadly.

The problem with valuing limitless economic expansion

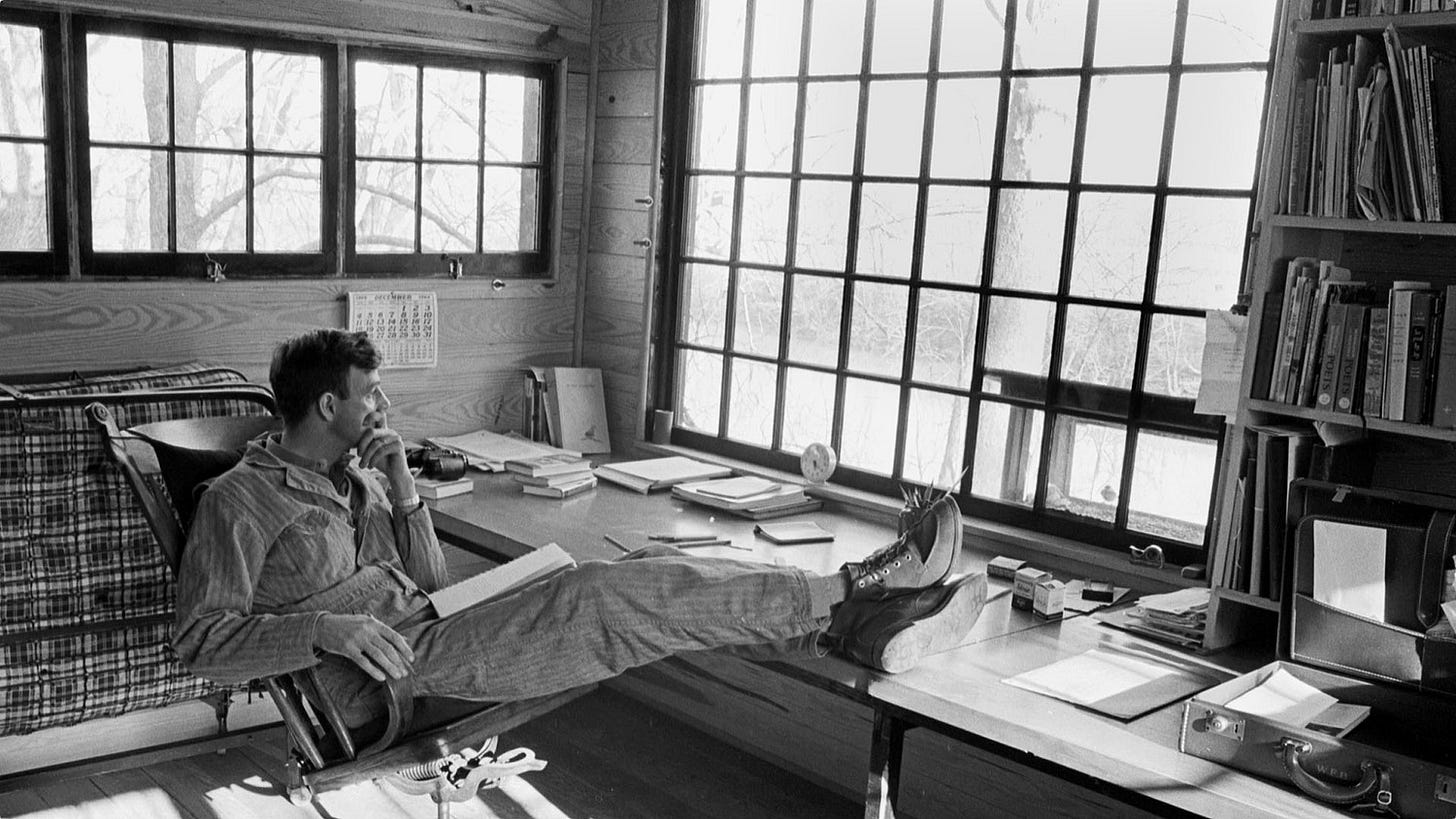

“It is impossible to escape the sense that I am involved in history. What I am has been to a considerable extent determined by what my forebears were.........I am forever being crept up on and newly startled by the realization that my people established themselves here by killing or driving out the original possessors, by the awareness that people were once bought and sold here by my people, by the sense of the violence they have done to their own kind and to each other and to the earth." - Wendell Berry, A Native Hill

It’s true we are who we are as a country largely due to the values embedded in our country’s foundation. And yes, those values involved conquest and unlimited economic expansion.

So is our problem merely one of values?

It's not that simple.

People's values are changing. They have changed. The civil rights movement, the equal rights movement, the climate change movement were all born of shifting values. The majority of the people in our country are not mercenaries hungry fore more violence.

The bigger problem is that the value of limitless expansion has been systematized in our institutions. And even though the values of Americans are changing, our systems make it extremely difficult to put new values into policy and action. As evidenced by the power of just 50 senators to stall common sense gun laws despite 90% of Americans (roughly 300 million people) supporting them.

And gun legislation is not the only area we are seeing the systemization of economic expansion valued at all costs, despite popular opinion:

Despite 2/3rds of Americans thinking the government should do more for climate change, the fossil fuel companies provide $138 billion each year to our government3- a fact that continually nips any substantial climate legislation in the bud.

Despite 63% of Americans believing that the government should provide healthcare for all citizens, the health insurance industry is a $31 billion per year industry and Big Pharma brings in $610 billion per year4. If equitable healthcare for all means limiting these profits, meaningful change is not likely.

Despite the majority of Americans not supporting the war in Afganistan in the latter half of the war, when the US government spends roughly $500 billion per year to weapons and defense companies, those companies have a substantial say in our defense policy.5

The NRA is arguably the most powerful special interest lobby group in the US6 and pays millions to specific senators to keep them voting against any gun control laws. Even though millions of Americans phoned their senators this week to push for gun control legislation, with our cemented national value of economic expansion- which is more powerful- hundreds of voicemails or millions of dollars?

So to say the problem is merely a values problem of the American people is not accurate. Rather, the cementing of the value of unlimited economic growth in our institutions is more likely to blame.

If you don't have the money, you don't have the power. And sadly, the NRA has FAR more money to spend than all of this country's gun control advocacy groups combined7.

So, what do we do about that?

Well, that's depressing.

What on earth can we do? Give up?

Wendell Berry would say giving up is not an option.

"We don't have a right to ask whether we are going to succeed or not. The only question we have a right to ask is what's the right thing to do? What does the earth require of us if we want to continue to live on it?"

If something immediately popped up in your mind when you read "the right thing" well then, hooray for you, go do it. But if you are left scratching your head between lots of "right things" and feeling stuck, let's take a lesson from Berry yet again.

Berry's solution to most of the world's problems is stronger, closer-knit neighborhoods and communities.

As it is, what little time, energy and money we devote to activism and world-bettering we tend to spend on the level where we have the least amount of influence- the national and/or global level. Leaving little of our time, energy and money leftover for the area where we could actually have the greatest influence- our local community.

While 67% of US citizens turned up to vote for the last presidential election, fewer than 15% turn up to vote for mayor and city council elections8 where their vote would have significantly more sway.

When we exclusively focus on areas where our influence is limited, we are more likely to give up and not impact the causes we care about.

"The issue of scale needs to be paramount, because it requires us to acknowledge our limits as human beings, as members of a species that is limited, and as individuals who are limited. If we keep trying for things that we can’t actually do, we hurt our causes, whatever they are."9 - Wendell Berry

Wendell Berry's solution to seeing his local land devastated by profit farms was not to save the entire world from climate change. Rather, he set to work to get to know all his neighbors, trade work with them, help them when they needed help. He didn’t give up on political activism. He just focused his efforts locally.

He petitioned against the construction of a coal-burning power plant in Clark County, Kentucky. The local petition was successful in prohibiting its construction. When he was 76, he spent a weekend locked in the Kentucky governor's office to demand an end to moutaintop removal coal mining.10

I'm similarly struck by the example of Montana Burgess, a Canadian devoted to impacting climate change. For years she worked for environmental nonprofits and attended international climate conferences. But she spent those years utterly frustrated that year after year nothing much really seemed to change at the global or even national level. So she decided to pack up and move back home to Kootenay, British Columbia.

She got involved with a local movement- the West Kootenay EcoSociety and eventually became its Executive Director.

She spearheaded a rather ambitious campaign- to get all local city governments in West Kootenay to pledge to commit to 100% renewable energy by 2050. After going door to door with a small army of volunteers, her campaign and petition were ultimately successful, even in rural areas where her efforts shockingly changed a lot of minds (a fascinating story that warrants a future essay).

When she focused her activism nationally and globally, she was forever frustrated, but when focused locally, her impact has been miraculous.

While national gun control legislation is slow, many cities are doing what they can in their own communities. Just since the Uvalde shooting, Sacramento, California hosted a gas-for-guns event handing out $50 gas gift cards if you turned in a gun, a church in Brooklyn over the weekend hosted their own gun-buyback event11, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina has allotted $50,000 to a drive-through gun buy back program.12

To re-cap

In a week filled with outrage, anger and hopelessness, a re-read of Wendell Berry’s timeless wisdom was right on time for me.

While listening to Nick Offerman’s melodic voice (he narrates Berry’s book), something inside of me shifted from blind desperation into a more clear-headed groundedness.

I find Wendell Berry’s 1968 declaration "It is impossible to escape the sense that I am involved in history” both a thought-provoking acknowledgment of where we’ve come from and a personal call to action.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank

Source: A Native Hill, 1968

Source: Resources for the Future

Source: Who Votes for Mayor

Source: Great Transition

Source: Democracy Now

Source: City of Winston-Salem

Oof I feel that call to action now, too!

I’ve been feeling that nihilistic sense of utter hopelessness for a while now. This came at a perfect time for me because I desperately want to fix the entire world and I get so frustrated/hopeless because it really isn’t possible to do as an individual. Thank you for reminding me that I can still make meaningful impacts in my community.

And, thank you for your writing. It’s so beautiful and each piece has been so impactful to me 🤍